The theory is that collective observations of anomalous phenomena can be explained by positing that all witnesses experienced the same, or similar, hallucinations at the exact same time, without any physical stimulus being present.

The idea of the mass hallucination is popular in entertainment media, where it’s often invoked as a rational explanation for supernatural phenomena.(1)

The problem with mass hallucinations, though, is that they don’t actually exist - at least not as we understand them. Although tossed around in everyday conversation, there is hardly any mention of mass hallucinations in the scientific literature. Some have speculated on the possibility, but there is very little scientific basis for the idea that multiple people could individually generate the same visual imagery and auditory information.

The science of collective hallucinations

But as blogger Douglas Mesner has noted in an excellent critique of the mass hallucination concept, a few scholars have suggested that it might be possible for crowds to agree on the details of a collective observation, even without everyone observing it for themselves.(2) This concept is sometimes referred to in the literature as a “collective hallucination,” although this concept too is poorly supported.

In 1895, Gustave Le Bon suggested that people in crowds are liable to enter a kind of hypnotic, and highly suggestive trance state, priming them for hallucinatory experiences.(3) Once someone suggests the presence of something - a sign in the sky, for example - then everyone else naturally accepts it’s presence. Enough people would succeed in hallucinating the image to create a convincing frenzy, and everyone else would just buy in to the hype, even without seeing the thing for themselves.

Psychologists Leonard Zusne and Warren Jones have referred to collective hallucinations in their book, Anomalistic Psychology: A Study of Magical Thinking.(4) Like Le Bon, they claim that collective hallucinations are only possible when large groups of emotionally aroused people are assembled in one place and primed by suggestion. The online Skeptic’s Dictionary has an entry for collective hallucinations as well, and defines it in much the same way.(5)

It would be highly unlikely for all members of the crowd to see anything closely resembling the primer’s description unless it were a highly detailed one, but the crowd would naturally, through shared discussion of the event, correct for discrepancies in accounts of the hallucinated imagery. Knowing what we know about the fallibility of human memory and our natural tendency to align our memories with those of others, it is not hard to imagine how a few hundred conflicting memories could be gradually harmonized over successive retellings.

Thus what allows the collective hallucination to really take hold in the crowd mind is not so much the witnesses’s failure to perceive what’s really there at the time of the sighting, but their failure to correctly recall the details of the sighting after it had already taken place.

The collective hallucination theory is not implausible, and could account for a few of history’s most most spectacular anomalous events. One such example is the famous Miracle of the Sun in 1917, a mass sighting that represented the culmination of months of alleged entity encounters reported by three young shepherd children. A crowd of 70,000 spectators were primed by the prophecies of the three children, and emotionally aroused by the suggestion that they had seen the Virgin Mary. That some people in the crowd agreed on witnessing a spinning silver disc, falling objects, and some colour distortions in the clouds, without any real-world changes actually taking place (and while staring into the sun!), is not beyond reason.(6)

The limitations of collective hallucinations

But it’s important to remember that collective hallucinations, at least as Zune and Jones define them, take place under very specific circumstances, and take their strongest effects long after the hallucination takes place. Not all anomalous observations occur under these conditions, and many are reported in such a way as to nullify the full effect of distortions through collective recall.

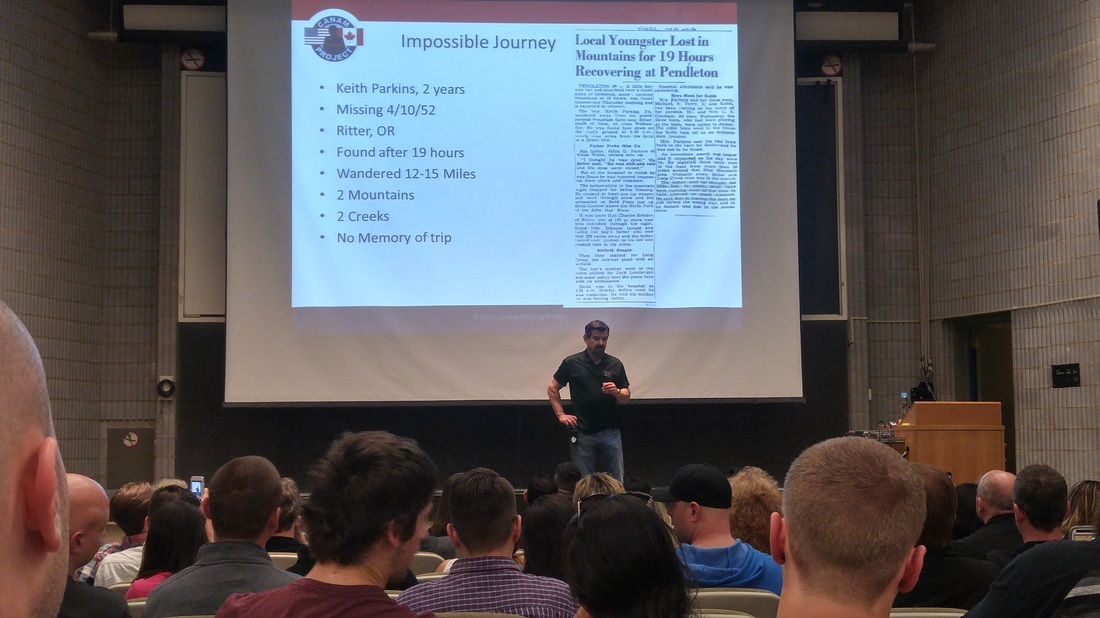

Unlike the Miracle of the Sun, most anomalous events aren’t presaged beforehand. The 10,000 or so residents of Phoenix Arizona, for example, who witnessed the “Phoenix Lights” had no warning that a giant, boomerang-shaped craft would drift over their city for two hours only on the night of March 13, 1997.(7) And viewing it individually, from separate households, they had no way of priming each other for suggestion, or of sharing their observations amongst each other.

Although the Phoenix Lights eventually spawned a media frenzy, police, news stations, and reporting centres received hundreds of calls before any of the news had gone public. Nearly everyone reported the exact same thing, at the exact same time. This assures us that the witnesses did not unwittingly converge their accounts in discussing it with each other. The crowd model of mass sightings can’t be applied in all cases.

It’s also important to remember that collective hallucinations have not been demonstrated through any kind of scientific process, experimental or otherwise. The whole theory rests on flimsy epistemic foundations. It is an extrapolation of the better-understood concept of hallucination without any unique data to back it up.

Hallucinations and hysteria

The idea that mass hallucinations are an accepted scientific phenomenon may well be the result of a confusion with the term, “mass hysteria.” Mass hysteria, a well-attested-to, if little understood phenomenon, is generally accepted as an explanation for the spread of certain beliefs, behaviours, and psychosomatic responses. It is not accepted as an explanation for group perceptions, visual, auditory, or otherwise.

For example, in 1518, some 400 people in Strasbourg, then a part of the Holy Roman Empire, were swept up in a craze that saw them uncontrollably dancing for sometimes more than a month without rest. Some died from exhaustion while others simply “danced it out,” but authorities were never able to determine what had caused the epidemic. The “dancing plague” seemed to be contagious, but nobody picked up any hallucinatory experiences.(8)

Another example comes from the West Bank of Palestine in 1983. 943 Palestinian girls and some female Israel soldiers complained of fainting spells and feelings of nausea. Although both Palestinians and Israelis accused each other of deploying chemical weapons, no cause was ever identified. Investigations concluded that while perhaps 200 of the earliest cases may have been due to real environmental contaminants, all subsequent ones were psychosomatic in nature.(9)

Again in this case, though many claimed to experience bodily symptoms with no discernible cause, no-one claimed to see or hear anything that wasn’t actually there. Our bodies and nervous systems seem to have ways of reproducing the experiences of others around us; our perceptual systems do not, at least not nearly to the same extent.

The mass hallucination theory: straw man, or honest confusion?

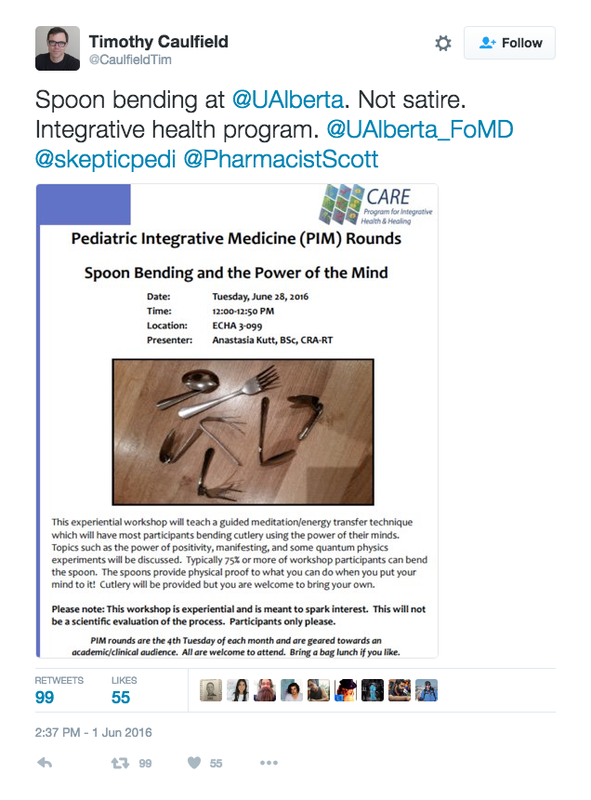

That “collective hallucinations” are so weakly supported in the psychological literature has led Mesner to question if the “mass hallucination” theory isn’t just a straw man argument employed by anomalists to make the only assumed alternative explanation - that the observations were true to reality - seem like the more rational choice.

I’m sure Mesner’s statement is at least partly correct. However, it has also been my experience that the mass hallucination theory is invoked more commonly by those who take a debunking position on a topic, but who also don’t necessarily understand the limitations of the collective hallucination theory.

Whether it’s used as a straw man or just confused with similar concepts like mass hysteria, there just isn’t enough scientific support for such things as mass hallucinations to accept them as a definitive explanations in any particular cases.

Conclusion

Good explanations for anomalous phenomena are built on good science and robust theories. The mass hallucination theory, in any name or form, is neither of these things.

In many cases, explaining group sightings as mass or collective hallucinations is about as speculative and ultimately pseudoscientific as explaining them as UFOs. It is not a more “rational” alternative to any supernatural explanation, and it should not be accepted as the default explanation for multiple-witness accounts.

- Jason Charbonneau

(1) For a list of references to “mass hallucinations” in popular culture, see: http://tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/SharedMassHallucination

(2) Douglas Mesner, “Mass Hallucination, Hysteria, and Miracles,” The Process is, published July 12, 2012, accessed Oct 27, 2016: http://www.process.org/discept/2012/07/12/mass-hallucination-hysteria-miracles/

(3) Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: a Study of the Popular Mind (Kitchener: Batch Books, 2001), 24-25: http://socserv2.socsci.mcmaster.ca/~econ/ugcm/3ll3/lebon/Crowds.pdf

(4) Leonard Zusne and Warren Jones, Anomalistic Psychology: A Study of Magical Thinking, 2nd Ed. (New York: Psychology Press, 2014), 114-118 and elsewhere.

(5) “Collective Hallucination,” Skeptic’s Dictionary, updated Oct 27, 2015. Accessed Oct 27, 2016: http://skepdic.com/collective.html

(6) Also noted by Zusne and Jones, 118.

(7) Lynne D. Kitei, The Phoenix Lights. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads, 2010.

(8) Paul Wallis, “Mystery explained? 'Dancing Plague' of 1518, the bizarre dance that killed dozens,” Digital Journal, published Aug 13, 2008: http://www.digitaljournal.com/article/258521

(9) Andrew Kincaid, “The West Bank Fainting Epidemic,” Oddly Historical, published on Dec 27, 2014, accessed Oct 27, 2016: http://www.oddlyhistorical.com/tag/west-bank-fainting-epidemic/

RSS Feed

RSS Feed