Bending Spoons and the Limits of Intellectual Tolerance

A few weeks ago, the CARE Program for Integrated Health and Healing at the University of Alberta posted a notice about an upcoming spoon-bending workshop on campus. Participants (mostly doctors, but other community members were invited as well) would be guided through a meditation that would enable them to warp a spoon with the power of their minds - and a certain amount of pressure from their hands. The event was the concluding presentation in a series exploring integrative medicine as a complement to conventional health care, and it was intended to be a fun activity to end on.(1)

The would-be presenter, Anastasia Kutt, an energy-healing therapist in Edmonton, Alberta (Western Canada), was prepared for a skeptical audience and hoping for an “educated conversation.”

She was immediately disappointed.

An outcry from skeptical tweeters pressured CARE’s director into cancelling the workshop and spurred Kutt’s resignation from the program. Meanwhile, the media amplified debunkers’ scorn in an over-blown and one-sided treatment of the controversy.

The #spoongate controversy demonstrates the narrow limits of our tolerance for unorthodox views in the modern university system, and offers a warning on the intellectually-stifling effects of suppressing discussion for appearances’ sake. It also raises questions about the role of academic institutions in regulating thought and practice, and implores us to take a more committed stance on intellectual freedom in the university.

The Spoon-Bending Workshop Controversy

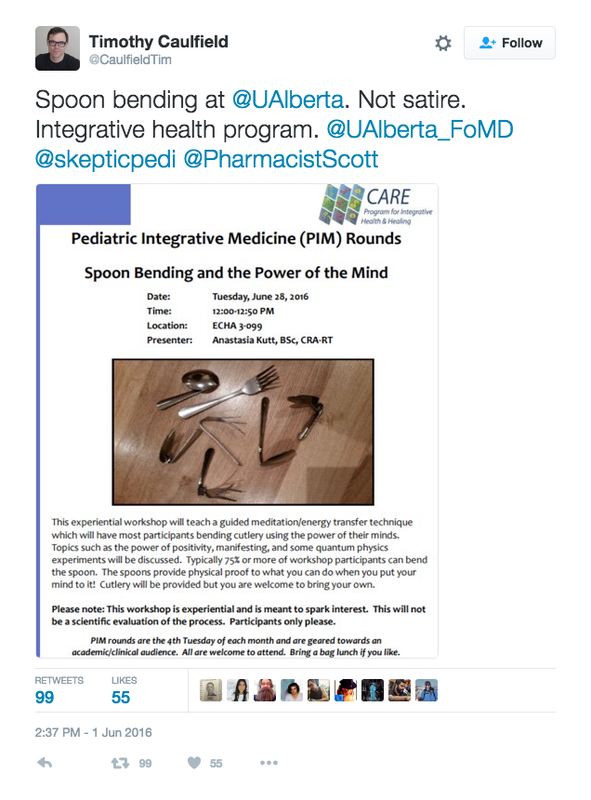

Sometime before June 1, Timothy Caulfield, a professor of health law and science policy at the University of Alberta, came across a poster for the event and took offence to its being taught at a “science-based” institution.

In an interview with the CBC, Canada’s national public broadcaster, Caulfield insisted that spoon bending has been thoroughly debunked, and expressed concern over the effect that hosting such an event would have on people’s confidence in university science. Whatever the university’s role in organizing the workshop (and Caulfield himself was unsure), he felt that even including the U of A logo on the poster was damaging to the credibility of the institution. “It really does seem like [programs like CARE] are part of academia and that, to me, is problematic.” (2)

The would-be presenter, Anastasia Kutt, an energy-healing therapist in Edmonton, Alberta (Western Canada), was prepared for a skeptical audience and hoping for an “educated conversation.”

She was immediately disappointed.

An outcry from skeptical tweeters pressured CARE’s director into cancelling the workshop and spurred Kutt’s resignation from the program. Meanwhile, the media amplified debunkers’ scorn in an over-blown and one-sided treatment of the controversy.

The #spoongate controversy demonstrates the narrow limits of our tolerance for unorthodox views in the modern university system, and offers a warning on the intellectually-stifling effects of suppressing discussion for appearances’ sake. It also raises questions about the role of academic institutions in regulating thought and practice, and implores us to take a more committed stance on intellectual freedom in the university.

The Spoon-Bending Workshop Controversy

Sometime before June 1, Timothy Caulfield, a professor of health law and science policy at the University of Alberta, came across a poster for the event and took offence to its being taught at a “science-based” institution.

In an interview with the CBC, Canada’s national public broadcaster, Caulfield insisted that spoon bending has been thoroughly debunked, and expressed concern over the effect that hosting such an event would have on people’s confidence in university science. Whatever the university’s role in organizing the workshop (and Caulfield himself was unsure), he felt that even including the U of A logo on the poster was damaging to the credibility of the institution. “It really does seem like [programs like CARE] are part of academia and that, to me, is problematic.” (2)

Caulfield’s reproach proved to be contagious. On June 1, he tweeted a screenshot of the event poster in a disapproving tone. The tweet - now retweeted nearly 100 times - sparked an outrage from the twittersphere, and specifically from opponents of alternative medicine.

Other tweeters were far more explicit than was Caulfield in his condemnation of “quackery” on the university campus. “Bending spoons is a great entry level activity. Sadly my med school taught science,” tweeted Clay Jones. “Solid skills for every physician to possess. Yikes.” remarked Susan Chapell, sarcastically. “I’m embarrassed to be from the same country,” tweeted Scott Stratten.

Others posted mock photos of their own attempts to bend spoon through intense concentration, and shared memes of the spoon-bending kid from The Matrix. Many tweets tagged the U of A’s Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, drawing institutional attention to would likely otherwise have been an under-the-radar event.

The backlash resounded in the skeptical blogosphere, where writers joined Caulfield in criticizing the university for facilitating the workshop’s organization, and presumably, for not putting a stop to it altogether. The very existence of the workshop was considered to be a breach of intellectual rigour. “Sure, it’s possible that a lot of physicians saw the spoon-bending flyer and scoffed derisively,” said David Gorksi at Respectful Insolence, “but the very fact that the workshop was scheduled is a symptom of a serious problem.” (3)

Then, just two days after Caulfield’s tweet, the Office of the Vice-president (Research) issued a statement reporting that the event had been “withdrawn by the presenters.” It was explained that the event had been organized in the absence of CARE’s founding director, Sunita Zohra, who immediately cancelled it when media backlash brought it to her attention. (4)

The same statement remarked that the event was about “reiki and other energy therapies, highlighting how and why patients and therapists use it… acknowledging that there is a lack of evidence about how, and how well, it works.” Kutt said that she had been asked to speak to this, and would make only a few remarks about energy healing at the outset of the workshop. The statement also made note of the fact that such Ivy League schools as Harvard, Yale, and Standard also engaged in research on “alternative medical approaches.” The statement reads like damage control, and a special attempt to convince debunkers of the CARE team’s compliance with mainstream medical opinion.

But this is not a scientific position; it’s a PR front. So what’s the science on bending spoons, and what’s the scientific value of testing these kinds of claims in an informal, experimental setting?

I don’t know if there is anything to the practice of meditation-guided spoon-bending; as far as I know, it’s never been tested. But that’s the problem: before Kutt was even given the chance to state her case, she was shouted down by those who imagined her as a potential opponent. We should all be concerned by the way that the #spoongate scandal has played out, and I’d like to come to the defence of Kutt’s would-be workshop, if only as a matter of principle.

In Defence of Bending Spoons

First off, contrary to what Caulfield has insisted, spoon-bending has not been conclusively debunked, at least not in the form that Kutt had promised to demonstrate it.

It’s true that a number of prominent “psychic” spoon-benders have been exposed as frauds, and that numerous stage magicians have revealed their tricks to be reproducible without mental powers. A quick Google search will return a number of videos by prominent debunkers like James Randi and Michael Shermer demonstrating how to fool people into thinking you’ve bent a spoon with your mind. (5)

Other tweeters were far more explicit than was Caulfield in his condemnation of “quackery” on the university campus. “Bending spoons is a great entry level activity. Sadly my med school taught science,” tweeted Clay Jones. “Solid skills for every physician to possess. Yikes.” remarked Susan Chapell, sarcastically. “I’m embarrassed to be from the same country,” tweeted Scott Stratten.

Others posted mock photos of their own attempts to bend spoon through intense concentration, and shared memes of the spoon-bending kid from The Matrix. Many tweets tagged the U of A’s Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, drawing institutional attention to would likely otherwise have been an under-the-radar event.

The backlash resounded in the skeptical blogosphere, where writers joined Caulfield in criticizing the university for facilitating the workshop’s organization, and presumably, for not putting a stop to it altogether. The very existence of the workshop was considered to be a breach of intellectual rigour. “Sure, it’s possible that a lot of physicians saw the spoon-bending flyer and scoffed derisively,” said David Gorksi at Respectful Insolence, “but the very fact that the workshop was scheduled is a symptom of a serious problem.” (3)

Then, just two days after Caulfield’s tweet, the Office of the Vice-president (Research) issued a statement reporting that the event had been “withdrawn by the presenters.” It was explained that the event had been organized in the absence of CARE’s founding director, Sunita Zohra, who immediately cancelled it when media backlash brought it to her attention. (4)

The same statement remarked that the event was about “reiki and other energy therapies, highlighting how and why patients and therapists use it… acknowledging that there is a lack of evidence about how, and how well, it works.” Kutt said that she had been asked to speak to this, and would make only a few remarks about energy healing at the outset of the workshop. The statement also made note of the fact that such Ivy League schools as Harvard, Yale, and Standard also engaged in research on “alternative medical approaches.” The statement reads like damage control, and a special attempt to convince debunkers of the CARE team’s compliance with mainstream medical opinion.

But this is not a scientific position; it’s a PR front. So what’s the science on bending spoons, and what’s the scientific value of testing these kinds of claims in an informal, experimental setting?

I don’t know if there is anything to the practice of meditation-guided spoon-bending; as far as I know, it’s never been tested. But that’s the problem: before Kutt was even given the chance to state her case, she was shouted down by those who imagined her as a potential opponent. We should all be concerned by the way that the #spoongate scandal has played out, and I’d like to come to the defence of Kutt’s would-be workshop, if only as a matter of principle.

In Defence of Bending Spoons

First off, contrary to what Caulfield has insisted, spoon-bending has not been conclusively debunked, at least not in the form that Kutt had promised to demonstrate it.

It’s true that a number of prominent “psychic” spoon-benders have been exposed as frauds, and that numerous stage magicians have revealed their tricks to be reproducible without mental powers. A quick Google search will return a number of videos by prominent debunkers like James Randi and Michael Shermer demonstrating how to fool people into thinking you’ve bent a spoon with your mind. (5)

All the techniques demonstrated in these videos, however, require the spoon-bender to be “in” on the trick, intentionally trying to mislead his or her audience. To the best of my knowledge, nowhere has it been shown how a group of doctors not willfully engaging in deceit could bend spoons through guided meditation, as Kutt claimed she could have them do. There is simply no basis on which to dismiss this claim a priori, as it’s never been previously debunked.

And there’s no reason to think that Kutt was putting anyone on, or making any attempt to explain the process by recourse to what some might consider “far out” theories like telekinesis. Indeed, she seemed to be every bit as curious about its cause as her participants. Kurt clarified her intentions for the workshop in a post to her blog just a few days after her resignation.

“Attendees at the workshop would have learned that spoon bending is not a “magic trick”, nor is it “psychic”. Anyone can learn to do it… I was excited to share and discuss this experience with the University community, and ask them – what do you think is happening? I was prepared for “skeptics” to attend the workshop, and was looking forward to having an educated conversation with them at the end…” (6)

Kutt claimed that several individuals in the medical community had previously expressed interest in the workshop. And why not? As Kutt pointed out, Health Canada estimates that over 70% of Canadians use integrative health therapies. Should our medical professionals not make some attempt to understand these therapies, and the non-materialist views that underlie them, even if they don’t believe them? By chasing alternative therapists like Kutt off campus, the medical community only risk losing touch with their patients’ views and beliefs.

As Kutt remarked, it’s a little strange that anyone would be so alarmed by the prospect of a group of doctors - presumably some of the sharpest, most educated individuals in our society - hearing someone out on a controversial claim. What are we afraid is going to happen if a few smart people are given the opportunity to apply their well-honed critical faculties? If spoon-bending is so obviously bogus, as Caulfield believes, then we should expect that the doctors would simply fail to bend the spoons and decide that the whole practice is bunk. Would this not simply strengthen their conviction in the radical separation of mind and matter, and reaffirm their own philosophical materialism? Would the medical community not be more dismissive of anomalous claims if more doctors saw their lack of efficacy for themselves? It’s difficult to imagine any harm befalling medical practitioners or the general public if the workshop were to go ahead as planned.

Separating Science from Pseudoscience

Running through the logic of knee-jerk scoffers like Caulfield is the assumption that there exists a clear line out there that cleanly separates science from pseudoscience, and that if people were sufficiently educated, they could all agree on where that line is. It is assumed by these same people that the university has some duty to police this line, and to ensure that the scourge of pseudoscience is never allowed to taint the purity of science. Avoiding pseudoscience is simply a matter of putting pressure on the right institutions to make the obvious, responsible choices.

It’s my contention that no such dividing line exists, and that we should not be shaming university administrators into drawing one themselves. There will always be debate on the difference between science and pseudoscience, and not for lack of education. It is an integral part of the scientific method that inquiring minds should disagree on particular questions and methodologies, and constantly re-examine “settled” scientific truths. We don’t need the administration to force a consensus by presenting us only with workshops that don’t challenge the majority’s views. If there will ever be a consensus on the efficacy of bending spoons with your mind, then we should be trusted to reach it through free debate.

As Kutt remarked, “the “skeptics” criticize many of these therapies for having no evidence, but when they are being explored in a university setting, they are bullied out.” Is spoon bending a real phenomenon? Can it be scrutinized by science? We’ll never know if we continue to drive its proponents from centres of learning, shutting down research and debate before they've even begun.

Tolerating advocacy for a particular position is not the same thing as advocating for that position, and censoring dissent is not the same thing as reaching consensus. We have nothing to fear from extending the limits of intellectual tolerance to include a discussion of what some might consider pseudoscientific practices.

The spoon-bending workshop should have proceeded as planned. Who knows, maybe some doctors would have bent their spoons. Maybe they would not have. Either way, we’d have learned something about the power of the mind.

- Jason Charbonneau

Published 2016/6/16

(1) Anastasia Kutt, Luminous Tranquility, June 6, 2016, http://www.luminoustranquility.ca/anastasias-blog. Anastasia’s website is currently down for renovations but can still be viewed at https://web.archive.org/web/20160902000926/http://www.luminoustranquility.ca:80/anastasias-blog. All quotes and references as taken from a transcript of the original blog post sent in a private message to the author.

(2) Mack Lamoureux, “Spoon-bending workshop, widely ridiculed online, pulled by university,” cbc.ca, posted June 3, 2016, accessed June 16, 2016, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/edmonton/spoon-bending-workshop-widely-ridiculed-online-pulled-by-university-1.3615916?cmp=rss&cid=news-digests-edmonton

(3) David Gorski (username Orac), “Integrative medicine and spoon bending at the University of Alberta and “Bigfoot skepticism,” Respectful Insolence, June 3, 2016, accessed June 16, 2016, http://scienceblogs.com/insolence/2016/06/03/spoon-bending-at-the-university-of-alberta-bigfoot-skepticism/

(4) Office of the Vice-President (Research), "Statement related to IHI and Cancelled PIM Rounds Workshop," blog.ualberta.com, posted by hbrodie June 10, 2016, accessed June 16, 2016, https://web.archive.org/web/20170723193442/http://blog.ualberta.ca/2016/06/statement-related-to-ihi-and-cancelled.html

(5) Michael Shermer, “How to Bend a Spoon with Your Mind,” YouTube video, uploaded by Skeptic Magazine, Jan 5, 2009, accessed June 16, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mxSNuIx4m5k; James Randi, “James Randi demonstrates how to fake psychic powers,” YouTube video, uploaded by HaulMorgan, Jun 12, 2007, accessed June 16, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJQBljC5RIo

(6) Kutt, Luminous Tranquility, see above.